Early Exploration - Crocodile Hunting in the Okavango Swamps

A 1957 expedition up the Santantadibe Channel in the Okavango Delta turns into a wild adventure of hippo attacks, treacherous floating islands, and close encounters with massive crocodiles. From patching a boat with condensed milk tins to testing a daring new crocodile-hunting method, this is Bobby Wilmot’s gripping and often hair-raising account of life on the untamed waterways.

Lloyd Wilmot

8/8/20253 min read

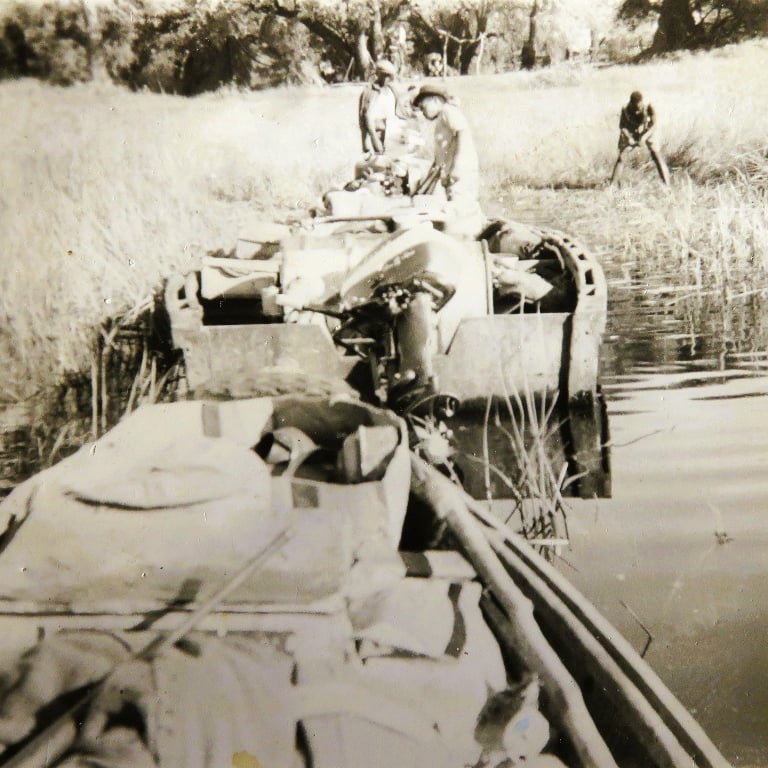

On this occasion, the journey began at Motsaudi, near Shorobe. We took the Santantadibe Channel, which enters the Thamalakane River from the north-northwest. My party consisted of Gideon, my coloured foreman, and six trained Africans. Two plywood boats, each fitted with a 10 h.p. Johnson outboard motor, were packed to the gunwales with fuel, gear, salt, rations, tents, and all the other necessities for days in the swamp.

The first mile, across the lagoon bright with water lilies, was peaceful. Beyond that, the 30-mile run to our first camp at Ditshiping was uneventful. This place—nicknamed “The Irons”—takes its name from the Mokutchom trees with iron spikes, remnants of Colonel Nous’s channel-clearing work 25 years ago. Nature has worked to reclaim them, but traces of his efforts remain.

That night, we began night shooting, pushing upstream each day to a new camp. By the fourth day, after wrestling the boats through lagoons and narrow hippo paths with overburdened motors, we broke into an open river—the Mborogha, near Xaba. This stretch borders Chief’s Island, winding upstream until a major blockage below Gaenga. Hippos crowded the water, and though game was scarce, we spotted lechwe herds and three shy, beautiful sitatunga. I am convinced that one channel flowing east toward the Mababe Depression forms the headwaters of the Khwai River, though papyrus blockages are common in that direction.

The water here rarely changes depth more than two feet between flood and low season. High upstream blockages seem to act as sluices, and in this flat, sandy country, the death of one channel often gives birth to others. Some lagoons reached depths of over 20 feet. Below the clear surface, the water quickly turned opaque with fine silt and decomposed vegetation. Gas from fermenting beds sometimes forces this mud upwards, creating fertile floating islands—sudd. These papyrus-covered rafts are favoured by waterfowl and young crocodiles, growing larger as flotsam and mud collect. But they are dangerous: some will not bear a man’s weight, and there are tales of people vanishing through the surface, never to be seen again.

I had my own brush with these islands. A day earlier, I fell up to my armpits through what looked like firm sand. Bubbles rose, carrying a foul stench, and I struggled to free myself. So when a bull hippo later punched a tusk-hole in my boat, forcing us to land on the nearest sudd island, I was far from pleased.

We were travelling up a deep, narrow stream when a family of hippos crashed out of the papyrus ahead. The bull surfaced immediately and advanced silently toward us. The men stood, shouting and waving, but the hippo came within six feet, staring us down for long minutes. Then, without warning, he submerged. We braced for impact—but he turned upstream to rejoin his family. We continued, but on the next bend, I saw him again, leaving his family to block our way. This time, my evasive turn failed. He rammed the boat just in front of the motor, lifting the stern clear of the water and throwing the men in a heap. My grip on the tiller was the only thing that kept me from joining them. The propeller struck his back but somehow held. We sped away, water pouring in through the hole. The nearest sudd island—thankfully stable—was only 100 yards away. There, we patched the boat with condensed milk tins and nails scavenged from the hull.

That night, we pushed on at 1 a.m., the river alive with hippos. Curiously, they now seemed more afraid of us than we of them, splashing away from our blinding spotlight. Crocodiles were another matter. Most we shot were scarred old males; females were rare here, the muddy banks unsuitable for nesting. Three times, crocs tried to seize men from the boat—once chasing us with its jaws agape until I put a bullet through its skull. Old bulls have skull plates two inches thick. A well-placed shot can dislodge this entirely, killing them instantly, though the tail often thrashes violently in death.

At night, crocs in shallow water can be teased to the surface by prodding them with a nkashe stick—an exhilarating but dangerous sport. Of 68 shots over two weeks, I killed 54 crocs, nine of them by this method. Stomach checks revealed lechwe as the crocs’ main prey, but also remains of baboons, warthogs, kudu, birds, and even polecats. Fish were rare—likely digested too quickly to leave a trace.

Along the channels, marabou storks were nesting, seven nests in just two miles, each with two chicks. I plan to bring rings for tagging on my next trip. Most nights, the spotlight dazzled various waterbirds—ducks, darters, egrets—allowing us to capture them unharmed for study. Such is the life of the Santantadibe: a place where the channels shift, the papyrus hides sudden death, the hippos claim their waters, and the crocodiles wait for the unwary.